Being back east is always a trip- both in the actual day long travel by air, as well as driving hours into the real wilds of an old New England woodland. While back east, I had the wonderful opportunity to visit some friends who bought land near New Paltz, NY. They finally got their house built and were able to host me for a few precious days of good reunion. Whenever I am in a landscape, my vision of what is and what was comes to life. This place has a long history of colonial influence and change, with little left of the original landscape to go by. Even in what is now a rural part of upstate New York, the evidence of human induced ecological genocide is all around. Thankfully, land can heal, will heal, with or without people helping, and it’s important to remember this whenever you encounter degradation. What might look like a typical hard wood forest, it a legacy of over-harvest, erosion, and chaos at the hands of early Dutch settlers trying to make a home in a place far from what they knew back in The Netherlands.

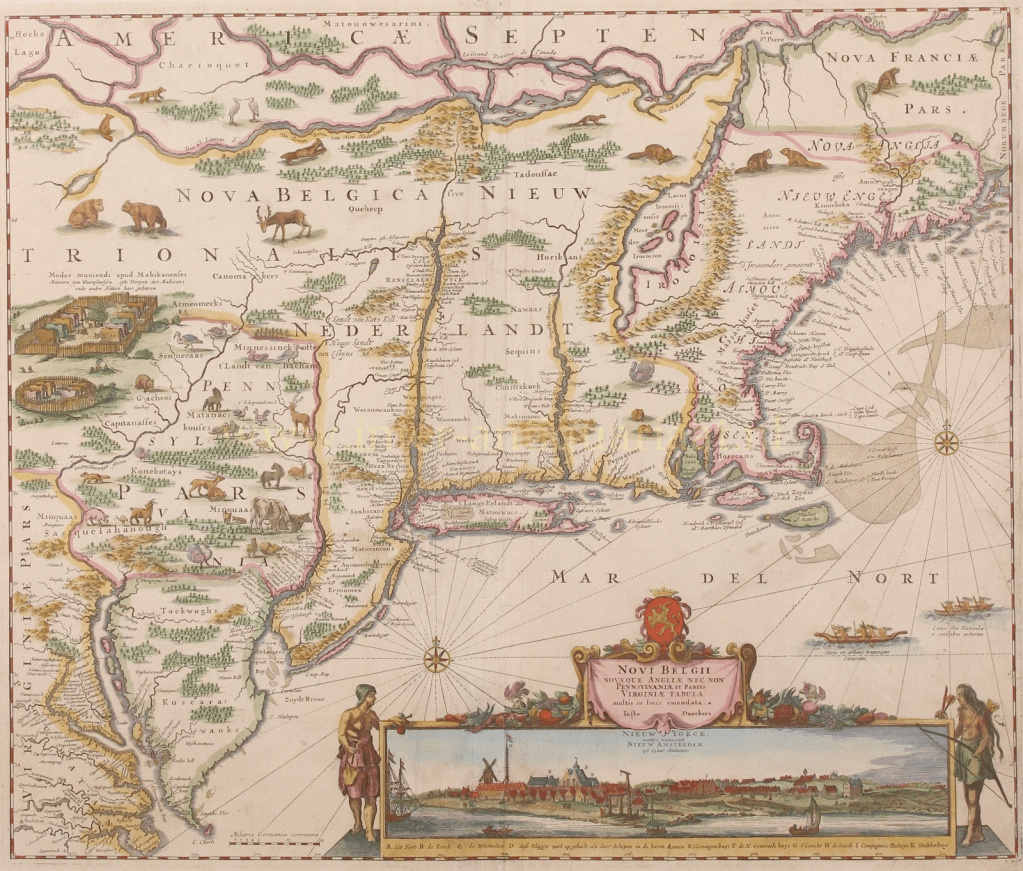

We have to first acknowledge the original people of the area, like all parts of America, First Nation’s were here before colonial invasion. The Haudenosaunee people, known as The Iroquois Confederacy, call what is now New York State, and much of the area around it, home. These tribes are still alive and present, both in their native lands, and in communities around The Country. Though we European late comers rarely see these people around, and often think they are gone, the tribes are active and aware, still seeking to be recognized and respected as the original tenders of this space, place, and time. Let us speak these tribes back onto the land, and carry their original instructions of land stewardship and community in our hearts as we stand now in the places they call home.

New Netherlands was New England’s big brother in the rush to settle The New World. Newness has a ripe quality of untouched, unspoiled- words of industrial opportunity and willed aggression. There’s enough out there about this struggle of European dominion over wilderness, played out in The Old World and still felt there today. I’ve written often of the environmental cost of colonial industrial resource extraction and how it plays out in our world today, and this post is no exception. See it.

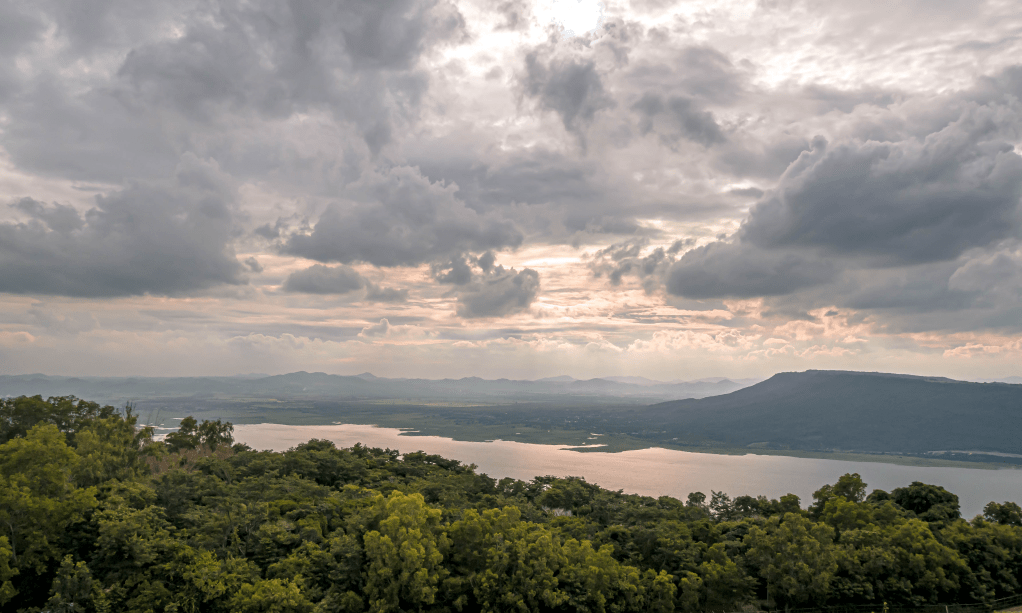

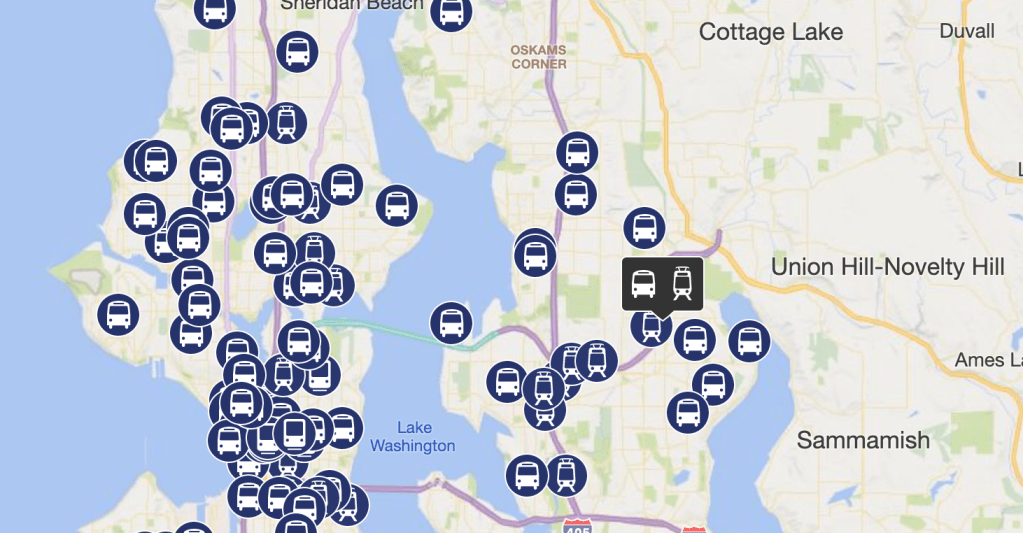

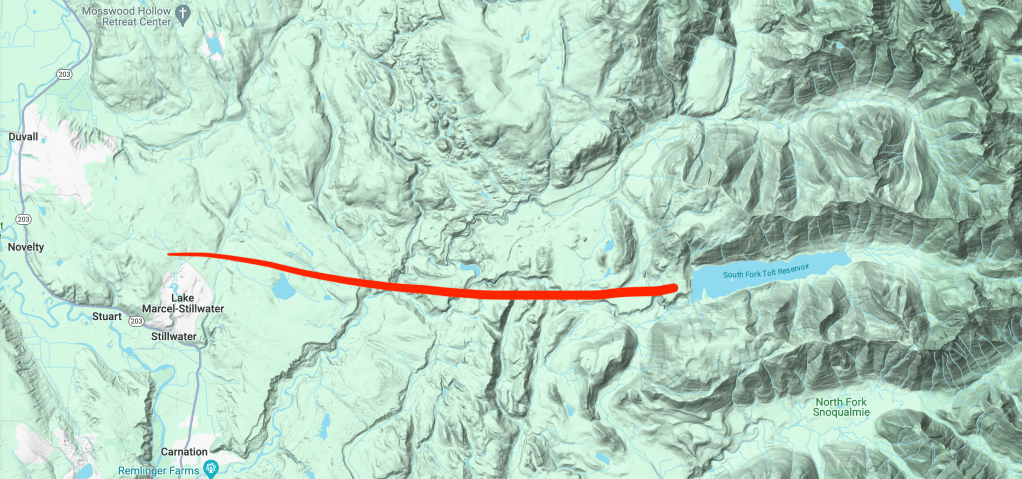

I stood looking down the sharp slopes, off the ridge that drops dramatically down to the creek below. Erosion hit this place hard after the initial clear cutting of the woods. It’s been cut at least twice, with no sign left of the old growth stumps. Such relics were burned, pulled, or slowly ground down under the hooves of overcrowded livestock. After the trees were removed, rains and melting snow came roaring down the gullies, carrying off rich topsoil and the seeds that would have germinated into new forests. In this particular landscape, now parceled into several properties of a few acres each. The Dutch grave stones tell of one family’s attempt to settle and manage a cherry orchard, shipping the fruit along the canal established in the 1800s, which connected to The Hudson River from Pennsylvania, and offered a direct water rout to New York City, once New Amsterdam. The building materials, coal, and agricultural products that left this landscape for the big city took quite a toll on the living world, but people made a lot of money, and progress was made. The farmers here were encouraged by the profitable markets, and set about straightening the creek and draining this marsh to create more arable land for production. Below you can see the creek and its unnatural straightness. I’ll also share a terrain map to see this creek compared to it’s untouched sister over the next ridge.

The family that settled here came from an ancestry of lowland dwellers; sandy bogs, tidal marshes, and expansive fens bordering the ruthless North Sea back in Europe. They were industrious farmers that reclaimed land by draining it, and that’s what they did here, even though it’s a far cry from tidal shore. Still, there is good soil in wetlands- peat moss and layers of rich organic material that can grow anything. Once drained, the land could be tilled and planted, or turned into good pasture for animals. Dairy was huge in this area of Ulster County, and with the advent of pasteurization, milk could be shipped by train. The area was booming economically, and maximizing anything off your land was paramount. I can only imagine the mud and muck labor that went into digging out these wetlands and establishing the cherry orchard.

By then, most of the American Chestnuts were killed off by blight, and the entire forest makeup shifted. Millions of animals would have starved to death without that crucial abundant nut source, and what was left by the mid 1800s was shot and trapped for meat and the dying fur trade. I say dying because fur trapping had already wiped out the prized fur bearing species like otter and beaver, fox and martin. Without the balance of predators, forest habitat, and healthy genetics from a thriving population, wildlife in the area. crashed, and what we see today is a shadow of what once was. What there is a lot of now, is ticks. I was constantly pulling them off me, shaking them out of my cloths, and checking everything that felt like the tickle of squirming insects on my skin. The ticks carry Lyme disease, and you don’t want it, trust me.

Another imbalance in this wrecked ecology is the age of the trees. There are no young seedlings or saplings in this landscape, well, a few beaches and crabapples, but no pines between germinated two inch seedlings and still maturing 80 year trees. I’ve encountered an ancient Eastern White Pine on the corner of a property in NH once, its diameter was 8 feet at the base. The branches of that majestic old growth pine are the size of the current mature stock in these woods. It’s hard to see what is not there, but young pines are a huge missing piece in this woodland, along with other young trees like oak and cherry. I tried to capture the amount of germinated stock that is present, as well as where it’s missing all together. On a drive through the area, I was able to see younger pines along the roadside in some places, so they should be present in our woods, but they are not. I hazard a guess they’re being eaten each winter by rodents under the snow, but that’s just a guess.

The leaf littler is slowly building up again, covering the ground to protect it from erosion, but there is still damage being done, and ruts of lost soil are growing every year. At the same time, there is attempted healing, as the erosion pulls down the banks, the trees fall in too, making mini dams and slowing the water on it’s way. In time, log jams will cause the creek to jump it’s banks, flood the surrounding lowlands, and in many more centuries of work, restoring the wetlands that once were. It will take more than vegetation to do this work, the native wildlife must return, and with it, the detail work of eating and pooping that disperses seed, churns up soil, and adds vital micro-nutrients to the soil for long term forest health. Vanished species like elk and the billions of birds that once darkened the skies on migration are necessary to return this landscape to what it once was, but this dream will not be reached, so long as people continue to develop and squander the land, rather than working with it, and returning the space to habitat for wild living things.

Like the small steps we’re taking at EEC Forest Stewardship, the small steps in Upstate New York can be pivotal to starting that rewilding. Replanting native vegetation, slowing and sinking surface water, allowing space for wildlife to live, seek shelter, breed, and raise young. Accepting we are only one small part of the complex living earth is the first step to seeing what you can do in your own small way to help return the natural world to a balanced state- and that state looks different to everyone, so finding common goals in your community helps tie together the end goal in conservation and restoration. As I’ve shared with these beautiful friends back in New York, your local conservation district is a great place to start. Most counties in The US have them, so look yours up and support them- invite them to your property if you steward land of any size, and if you don’t have land, you can still volunteer to help protect lands that are in the care of your conservation district, which is still making an important contribution to conservation in your area.

The adult pines are still dropping their seeds into this forest, making space for a new generation each year, and in time, with some help for land stewardship practices, younger trees can begin to return, and a wetland can be restored. Imagine the possibilities once a landscape is back on track to becoming whole. Well, you don’t have to completely imagine, here are just a few examples of active restoration work that has saved wild places all over our country, and the world. Coming back around to this little forest and stream in upstate NY, I’ve shared a vision of BDA (beaver dam analogues). Slow the water, meander it into the wetlands to sink in, and allow the natural habitat to restore over time. It’s a small step in the right direction for a landscape patiently waiting for some TLC.

The people that settled here in early colonial pushed inland to exploit natural resources were caught up in economic schemes for personal gain, and to be clear, that’s still a thing all over the world. But you can stop this cycle by not participating or supporting thoughtless exploitation through voting for progressive conservation minded politicians, donating time, treasure, and talent to your local conservation organizations, and spreading the word to family and friends. Though the legacy of our ancestors has left a lot to be desired, there is always opportunity to change out ways. Please join me in working towards restoration, it’s the best way to heal our earth and ourselves through re-connection to our own rewilding too. Much gratitude to this wild earth for continuing, especially those white pines still dropping seed each year for a new grove of young trees that might one day come. Thanks to all the original people of this landscape, who remain, and keep asking for better stewardship and land back practices that help return our lands to wilderness for a future where people, plants, and animals all thrive together in an intact natural world.