Yes, a surprise two day trip to visit family and I’m back in the air again- biggest carbon footprint I can make. I try to make the most out of these moments, so I grabbed a window seat and looked down. I knew it was going to be wild scenes in Puget Sound, freshwater outflow from flooding rivers carried sediment deltas far out into the ocean waters. The tides push back, but it’s fascinating to see just how much soil is going into the ocean from 50 miles inland or more. There’s also human and animal sewage, vegetation, dead animals, trash, polluted runoff from roads, and much more. I’m sure the coloration of these plums says something about their makeup, either way, it’s dumping into harbors and clogging waterways. Nature continues her rebellion against our abuse, and it’s easy to see the bigger picture form a few thousand feet up.

There’s a fresh snow on The Olympic Mountains, and also on The Cascades, near where I live. This snow pack is crucial to survive the summer drought, but the snow is late, and even the ski industry is getting hit this year as mountains remain closed into December. Hopefully this first snow stays, and gets added to often throughout the next few months of Winter. When we don’t get enough snow, the river valleys shrivel to nothing, and it does not really matter how much flooding happens now, all that water flushes away into the salty sound, and ocean beyond. In some places, like EEC Forest Stewardship, we retain the water, slowing it with earthwork swales, then sinking it into the soil, letting the plants drink deeply, storing the water. If we designed all the ground like this, we could keep water on the land where it falls, banking it into the ground to help maintain a strong water-table below.

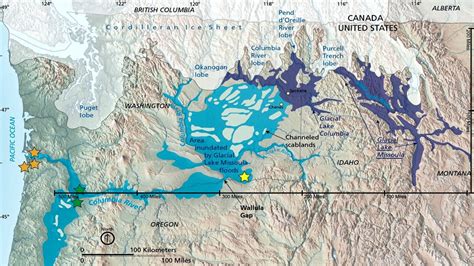

Water has been a huge influence on sculpting this landscape as glaciers ground the geology into pebbles and ice age floods scoured the land. Drumlins are easy to spot from a plane, and I took full advantage of flying over them with enough visibility to snap a photo or two. Since I was headed to The Southwest, we flew down into the Oregon end of Glacial Lake Missoula Flooding. Looking closely, I can pick out the river bottom ripple effect of the massive waters cutting across the landscape. These dynamic changes are nearly impossible to fully comprehend, as we’ve never seen water of such volume in recorded history. The First Nations of the area do have oral histories that tracked glacial retreats and migration up and down the coast and inland valleys in their canoes and on foot further east in the high desert, thousands of years before Spanish conquistadors brought horses.

In early December, 2025, atmospheric rivers flooded The Cascade Mountains for weeks, and the lowland valleys below. This flooding was no where near what the melting ice sheets delivered in a single major flooding event, but Western Washington got a glimpse at how water takes over a place, filling space and blanketing vast areas with sudden change. Thankfully, EEC was not in any flood danger, but witnessing some of the chaos from the air as I flew south, gave a lasting impression.

As my flight continued, passing over Western America from 40,000 feet above, I was able to witness other climate fueled changes going on across the landscape. Over Utah, The nearly dried up Great Salt Lake is caught in a polluted disaster as winds whip up the dry lake bed where countless toxic sediments await a chance to fly. When this happens, air quality plummets, and being without filtration masks or an h-vac environment will cost local residence their health and well-being. I knew my flight path would take us very near Salt Lake City, Utah. As we crossed over this vivid landscape, I began to see the dust clouds rising between the vapor clouds at low altitude. At first I thought they were wildfires, but no flames appeared below. The wind was carrying up the dust and spreading the heavy metals and corrosive chemicals left in the lake bottom after two centuries of industrial abuse and environmental neglect.

Perhaps we think, in our short lifetimes, that these catastrophic environmental collapses will not bother us directly. It’s already costing us, from insurances of all kinds, to the environmental pollution that causes so much of the health problems we face at younger and younger ages- effects not easily measured by science, due to the expansive variables involved. Half the population in The USA suffers from poor air quality. You may be living in what you think is a pristine environment, but the legacy of industrial greed and corporate extraction haunt not only the air we breath, but also the water we drink, and the food we eat- all of which remains exposed to our own polluting habits. Flying on an airplane is not helping, as I said earlier, it’s one of the worst impact I can make as an individual at this time on Earth. Where have we gone so far off the rails? In one word- population.

Let’s take a trip back in time, to a place in The Southwest of America where prehistoric humans thrived in a different climate, one that today may present as high desert, but was once a lush savanna with thriving populations of grazing animals and clean environmental quality. Tsankawi is a magical place I’ve written about before. As a avid outdoor enthusiast, I am draw to places where early peoples lived and thrived when the environment was conducive to such habitation. The site is an entire small mesa complex that would have had a flowing stream on the south side with canyon walls to drive herds towards easy to hunt bottle necks along the waterway. 360 views from the top of the pueblo secure the area from all direction against raiding and ambush. The stone age people who first established residency in the cliff caves would have thrived in a time of more rain, better vegetation growth, and many more animals to hunt. They would have been dabbling in early agriculture, as well as hunting and gathering throughout the region.

Life would have been mush more challenging over ten-thousand years ago, but it would have also been short and sweet. I can only imagine that during a lifetime in this stone age village, a person would have deep connection to place, the plants and animals that sustained them, and strong connection and belonging in the community to survive. How can we rekindle this connection in our own lives today? Can you cultivate anything in soil where you are? What is the source of your drinking water? Where does your food come from? Do you have a larder for emergency? What kind of birds sing near your home through the different seasons? These are only a few questions out of many we can all be asking ourselves to reconnect with the natural world, and better see our relationship to it. We may thin more about a grocery list than setting a trap for a rabbit or foraging for wild grains, but the sources of our food still come from land worked by other people to keep us fed, and those crops can and will be directly impacted by our actions day to day.

The people who established the cliff dwellings at Tsankawi eventually abandoned the area by the 16th century, about the time there was a sever drought across most of The Southwest. The exact reason for human depopulation throughout the region is still unclear, but unrest was the outcome, through many of the surrounding First Nations today claim the stone age people of Tsankawi as ancestors. The high desert now well established in New Mexico does not lend its self to massive populations, but in prehistoric times there were many more natural limitations to massive growth, from infrastructure to the variable climate and unstable early agricultural. Too many people in an area depleted wildlife through hunting and trapping, until a lack of food would force displacement. When resources became scarcer, raiding would increase, making permanent settlement vulnerable to attack. The larger a settlement, the larger the demand on the natural world, which, when left unchecked, depletes everything until famine and starvation take hold. Ecological collapse often plays a role in toppling civilization, and without food sovereignty, all populations are susceptible to this looming threat.

The United States has an unbelievable arsenal with weapons of mass destruction for all. Just a few miles from this site, the birth place of atomic weapons continues its quest to stay ahead in the arms race. The current indigenous nations of the area remain on reservations (pueblos), through they continue to quest for their access to sacred sites and the resources needed to remain connected to the land through hunting and gathering, as well as agriculture. They also have strong spiritual ties to this place, where ritual and traditions are still practiced. I am so grateful to know these people are still present and active in the area, and continue to voice their concerns about colonial treatment of the earth and the impact of military occupation today. Reflecting on our personal lineages and how we directly or indirectly benefit from the removal of indigenous people from their traditional homelands over the past few centuries. My ancestors came from Europe on boats through Savannah Georgia and moved west from the 1700s through the 1900s, ending up in Oklahoma, where many First Nations were sent as eastern states filled up with European immigrants after initial colonization of The East Coast.

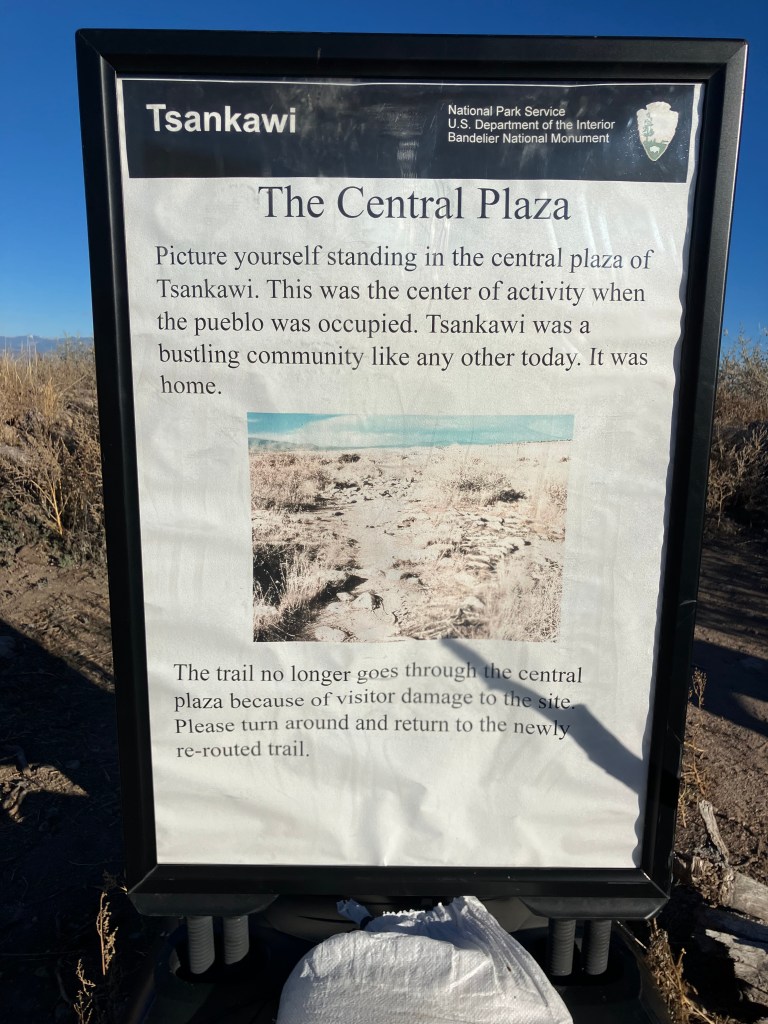

Right now I am sitting on stolen Snoqualmie Tribal lands that were carved up by timber barons in the late 1800s, along with railroad tycoons looking to cut a way through the big trees to ports along The West Coast. Legacies do matter, and our ability to name our ties to them, to see how we live in the wake of them today can be a powerful and ongoing lesson. It’s a chance to reflect, take in, and respond. My response is to stand in these sacred places to learn from the statements being erected by the original people, who are still here and willing to speak to us, to ask us to listen. They are slowly putting up their own boundaries, offering insight, and reminding visitors that the land is still part of their heritage. When I summited the cliff and stepped to the edge of what was a later pueblo structure, there was a new sign up with a clear message to go no further. Though in past visits, there were walking paths into the central plaza, now a clear direction to keep out reminded me that people are not always respectful guests.

I’ll remind us that National Parks, like Bandolier, were never discussed with the local indigenous people that once lived there. Whole villages were often removed from the wild places we call park today. Though parks do preserve important wilderness, the people that lived in deep connection with those places, were part of the wildness in them, have been taken away to offer an illusion of pristine wilderness we like to think of as untouched. Some states are working to change this assumption by teaming up with local tribes to change public understanding of parks and why they disenfranchise many indigenous people who once inhabited what are now National Parks. Tsankawi remains part of The National Park system, and visitors pay a fee to be there, but local Pueblo People also come to practice traditional ways in the area, and remain connected to their ancestral place. Where are your ancestral places?

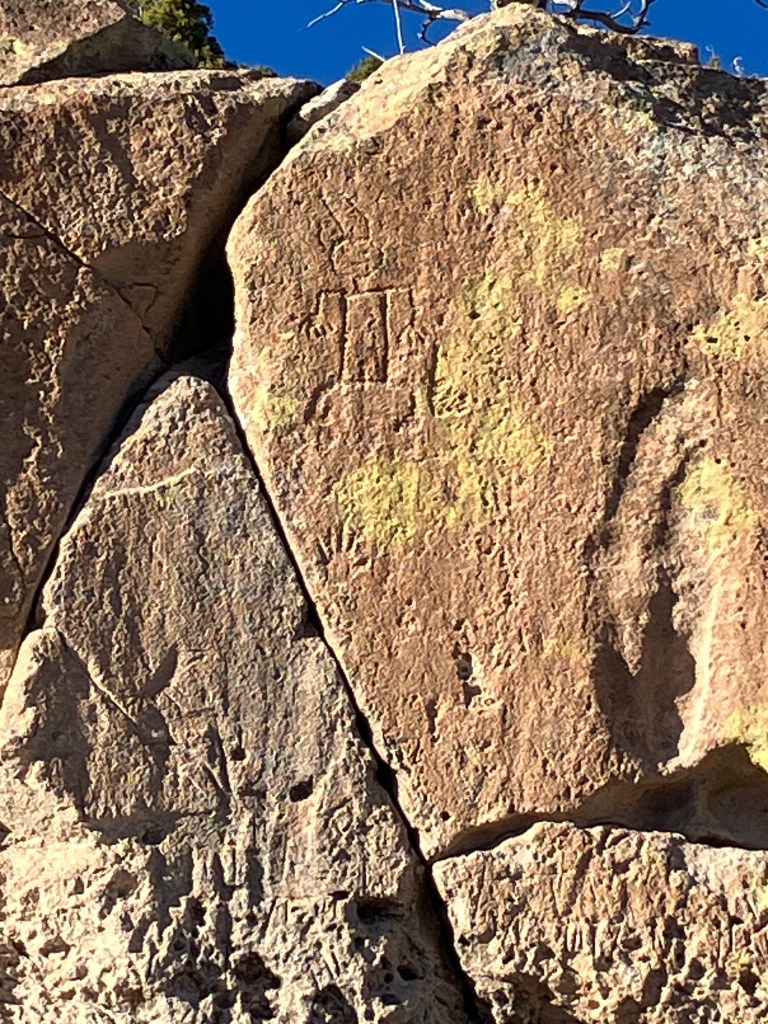

The petroglyphs are yet another reminder that ancient people lived here and were deeply connected and reliant on place for shelter, food, water, family, and community. We can all relate to these needs in our lives today, but most of us will never carve sacred symbols into the wall where we live in reverence to the space that holds us. When did you last make some lasting rock art to communicate? When did any of us last sleep in a cave? I took the opportunity to sit in one at the site, looking out across the landscape while imagining what it would be like to tend a fire there, cook some venison, and talk with friends and neighbors late into the night, sharing stories of long journeys successful hunts, and celestial navigation. When was the last time you slept under a blanket of stars? This place truly inspires me, and helps craft some personal dreams to reconnect, share, and spend more time outside with others. Though I came to the monument alone, I met others on the trail who stopped to talk and reflect on the experience in this magical place. We stood in awe, appreciating the beauty and human presence literally carved out of petrified pumice. Below is a footpath up the cliff side that has been worn down over centuries of use. There are many paths like this along the way in this loop trail, and the feeling of following those footsteps drops me right into prehistoric life thousands of years ago.

I’d flown a few thousand miles to be here, and celebrated another incredible trip to one of my favorite prehistoric sites on earth. The opportunity to be in a high desert terrain full of early human settlement and a legacy of connection to the sacred rejuvenated my own vision to place connection back in Washington. I chose to live where I am because of the abundance- water, temperate rainforest, ocean, mountains, rivers, lakes, and high desert on the other side of The Cascades if I want to dry out and find the sun again. What privilege! We can all be grateful to access- public parks, public lands, public education. Let’s try to spend more time in public, being present with place and those who share it with us.

As the flood waters receded, I returned to The Puget Sound and found it raining again. I love water, and am thankful for all its gifts, even when it seems like we’ve had too much of it. The sacred floods are a part of this land’s great history, along with massive ice sheets, monumental great floods we can’t comprehend, and a lot more to come. From strata volcanoes to some of the most active fault lines on earth, Western Washington is a heck of a place to call home, and I’m grateful for it every day, and the opportunity to share these adventures with you dear reader- thank you for your time and interest.