Red Cedars are capable of great feats in adaption to survive. They are often leaning out, way over the rivers and creeks throughout Western Washington, spreading their branches to lend shade to the waters, keeping the temperatures cool for the fish and other aquatic life. When a landslide occurs, cedars thrown sideways downhill will re-root in whatever position they find themselves in, sending out a new crown lead if things go topsy-tervey. Often, when a tree falls over, it becomes a nurse log for other young vegetation. When left to grow upward and stretch existing branches, the skirt of the tree will bend down to the ground and re-root over time. It’s rare to recognize this action in nature, because most of the red cedars were cut one-hundred years ago, and the younger sapling trees around them- the branches that re-rooted, were cut like any other trees in the stand. You have to find protected areas like old homesteads that became county parks.

The picture above is a wonderful example of branches re-rooting and becoming braces for the existing tree, and establishing more stability and nutrient sharing. The smaller branches go into the ground at the curve of the “J” and with the continued replenishment of topsoil on the original homestead where this tree is located, the branches rooted and became maturing trees, growing much larger from their new rooted bases. For this kind of low branch development to happen, the cedar must also grow in an open area, where light is available all the way to the base of the tree. Mature old-growth forest offers little direct light to the ground, and the usual growth patterns of trees within a woodland look more like the following diagram.

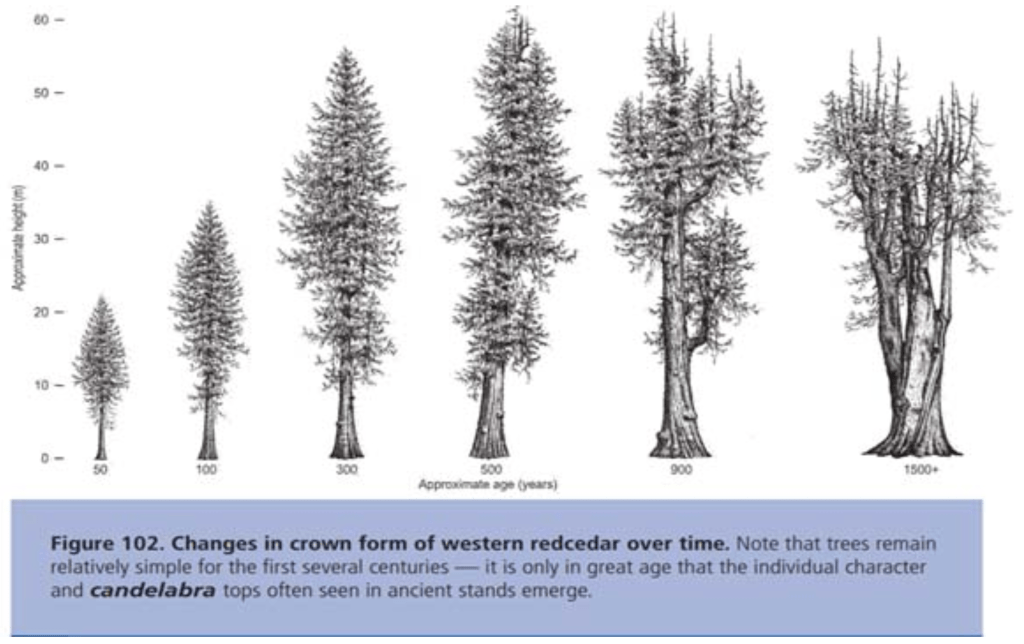

It’s always humbling to think Western Red Cedars would grow for thousands of years if left to do so. The lone field cedars with rooted branches, will need the added support standing alone in a field. I’ve also seen branches at 90 degree angles off a tree near the base in thicker woodlands, perhaps where a patch of sunlight did filter through, and the cedar stretched towards it in desperate competition. Up is always the best direction to grow in a forest, and the outstretched branch turns up to follow the light. Even the candelabra shape of ancient trees shows a continued push ever upwards. I’d also like to point out this tree’s preferred habitat in or near wetlands and in flood planes where open edges of water invite the cedar ample space to extend branches into open sky.

At EEC Forest Stewardship, many of our cedars retain a skirt with j branches arching towards the earth. They set a goal in forest duff creation to raise our topsoil regeneration level until these lowest branches are buried and rooting out. This vision is worthy of generational scope, and will take tons of vegetative input to achieve. Starting with layers of moss, twigs and branches, as well as ground-cover plantings mentioned earlier, we aim to recover lost mulch and debris which a healthy forest needs. It’s a grand plan, and I’m sure we’ll have some great examples later this fall as we work to replant the understory. In the mean time, keep a sharp lookout for rooted branches in your own neighborhood or local park. Many species do this, so take note of forest shape, location, and history.