Cascade Katahdins are chowing down on blackberry in another summer onset of overgrowth. A weed-wacker is assisting in breaking down some of the cane to mulch. Overall clearing success continues, with the slow, manageable replanting in hazel dominate hedge,, big leaf maple deciduous edge, and Quercus garryana savanna. The sheep love everything they can sink teeth into; filling a complex gut. Katahdins are browsers, so they really get into bushy places and nibble away the green wall into more of a collapsed lattice that is easy to chop and drop. This sheep is a best friend to our forest in recovery. After seven years of goat clearing, the Katahdins moved right in and, using the goat accesses, ate there way through the gaps and clearing edges to keep pushing back brush with enthusiasm. We can’t say enough about this breed in Western Washington and how perfect it is.

The work right now focuses on an area we’re prepping for our future Cotton Patch Geese. The small paddock takes about three days for the sheep to eat down, but more work could be done with electric mesh pressuring. With a little more weed wacker work, the pasture will open up enough to host almost a half acre of grazing pasture, but Katahdins are not put off by bramble completely, and enough of a dent was done in this grazing cycle to make the mechanical clearing work manageable. We’re also monitoring a knotweed stand, which is cut down and eaten regularly. The Katahdins also love this invasive as a snack and have kept much of it out of our pastures.

This enclosure was once over head height in blackberry, with a resident Aplodontia rufa, who left soon after the goats moved in. I had hoped to see it down in the creek buffer, but it could have been predated, especially as we opened up the space. Mountain beaver are one of those prehistoric creatures you didn’t know still exists- especially when you realize they are almost blind and deaf. Sadly, these animals are considered a pest by the timber industry, and are often poisoned and treated as vermin. They play an important role in aeration of soil, and swordfern control, and are actually a threatened species. This animal has a very intimate, and ancient relationship with temperate rainforests. The impacts of my domestic stock on their relationship with the landscape cannot be ignored. This specific area of the land is a major replanting zone for our restoration forest plans. We hope that within this lifetime, we’ll have a fully planted stand in this space to celibate.

The sheep play a role that can be too much of a good thing, and it’s so important to know when these veracious browsers should be pulled off the land to give the plants a break. It’s also crucial to keep an eye on the types of plants you’re letting your animals onto. The major pasture areas at EEC have a legacy of overgrazing. There’s not a lot of ground cover or sapling trees present. Moss has a firm hold in the shady areas, and blackberry thrives on the sunny clearing edges, hoping to close in on any open fields. A few oso and elderberry shrubs are established above browsing height, but still take a browsing hit from the sheep- filmed above. If the sheep stayed on this pasture space indefinitely, that oso would be pulverized and eradicated. To establish any ground species where sheep graze, I have to hard fence the space or hot wire during the growing season. Sheep will eat anything lush and green- especially young growth, like new starts. My gardens are all hard fenced to keep the sheep out, and you should fence anything you don’t want them getting into- because they will.

Below is a photo of where the sheep have browsed (on the right of the fence), compared with where they have not grazed on the left. You can still see some green in the eaten area, but it’s lost it’s lush spread, and need a break from grazing before the sheep start grazing down to grass root base and push down branches of the young trees and shrubs. Our brows crowd has no limitations of it’s own, so it’s up to the shepherd to move the animals and gauge the land’s plant phenotypic plasticity. Drought is making our pastures more vulnerable to overgrazing, so the sheep have to be rotated more often, shrinking the amount of pasture time we have avvailable for the animals, meaning we have to reduce numbers of animals. Commercial operations (USDA “small” operations are 500 animals) can’t flex instantaneously to those fluctuations, and are often denigrating their lands under the increasing pressures on our environment. This goes for all agriculture, not just livestock.

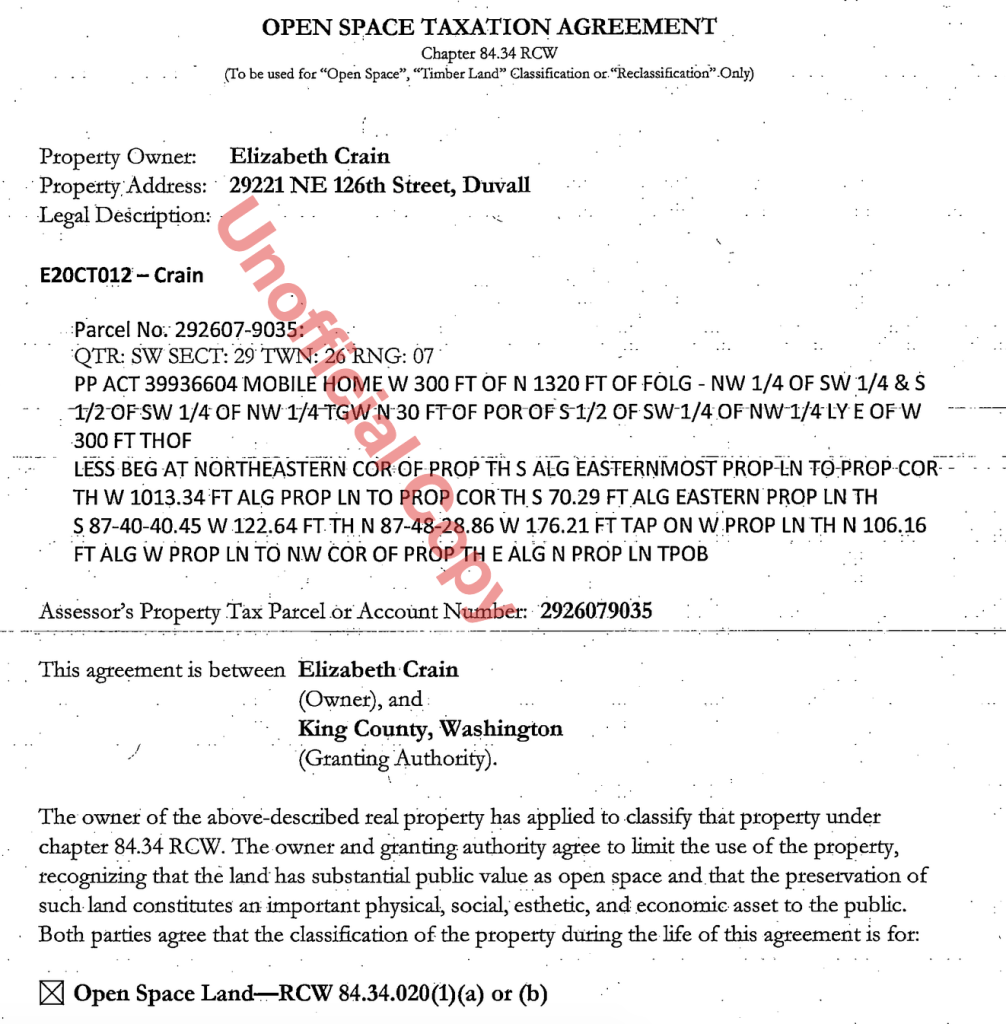

I’ve been witnessing more and more surrounding properties with livestock showing the tale tell signs of degradation in gurtled trees, moon dust pasture lands, and compacted bare soil. People seem oblivious to the drought conditions in our area, and are not planning for 90 degree six month summers. They are not irrigating, and are not taking their stock off the pastures soon enough. Here at EEC, we are doing all we can to prevent degradation, replant and restore through rest and rehabilitation. If we took all the livestock off the land tomorrow, we’d still be obligated to mow the pastures to keep them open under our agricultural agreements with the county (detailed in our open space plan which you can find here under parcel ID: 292607-9035) Below is the main agreement page.

With the help of our Brows Crowd, we will keep restoring the landscape with responsible livestock systems and some wonderful long term vision of restorative planting and tending towards abundance. Gratitude to all involved in supporting this process, from Mother Nature to my own Mom, the sheep, pollinators, wildlife, winds, waters, and woodlands- all is good and gracious in this place.

So fabulous to read about all your accomplishments over the years of planning and executing sound practices.

Congratulations and May it continue to proceed in the best fashion possible.

With love from Paris…

LikeLike