In the continued adventures of exploring new parts of Washington State, we took a weekend tour of The Green River Gorge; staying in Kanaskat-Palmer State Park, and visiting the abandoned mining town of Franklin, now owned and managed by the state. Ancestral home of The Duwamish Tribe, now The Muckleshoot, there is only the watershed title left as any legacy to First Nation People in the area. Dubious treaties restricted and removed tribes from their ancestral lands. Tribes thought they would receive reservation land around The Green River, but by the 1880s, corporations had founded towns and dug mines deep into the area with no plans of giving up the land to “savage Indians”.

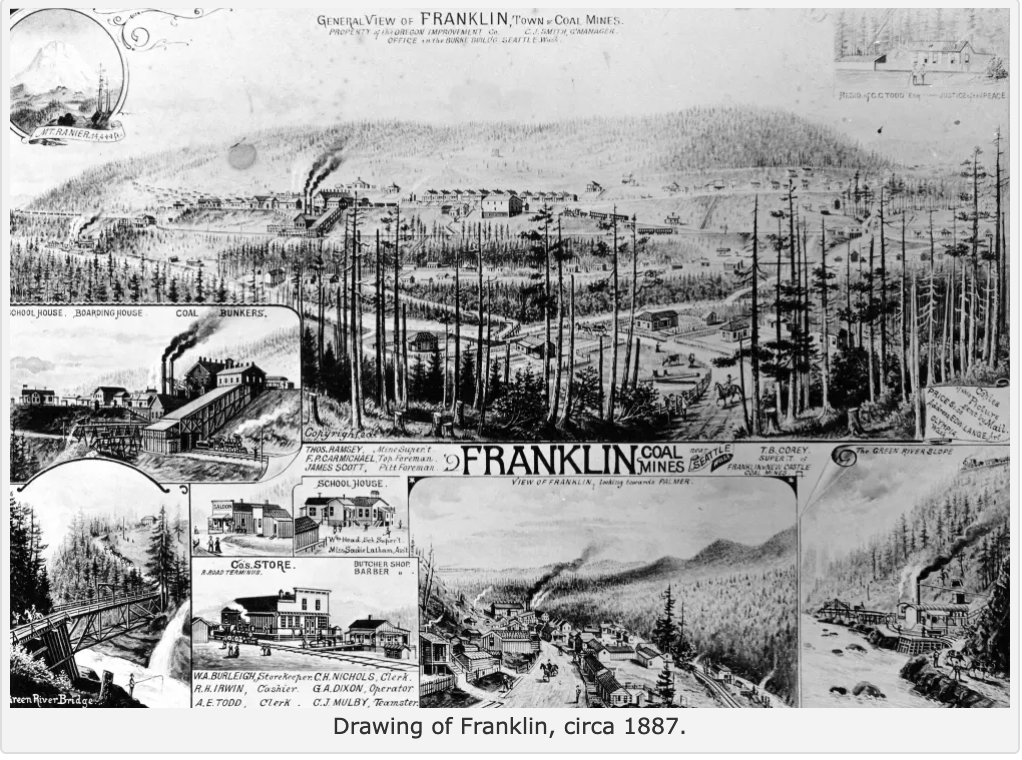

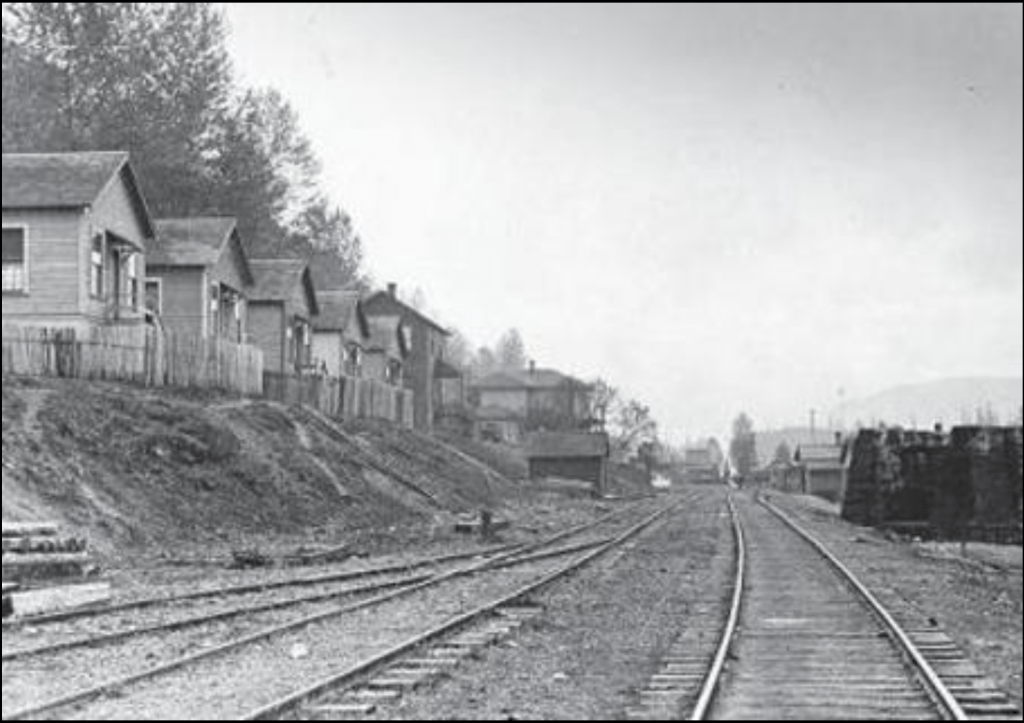

One such town, Franklin, WA, struggled with miner strikes and eventually, in the 1890s, black miners from the eastern US were shipped in to cross the picket lines. Ernest Moore wrote about his African American family in Franklin coal mines, though the book is now out of print. The town was failing again by the early 1900s, as the demand for coal waned, but during WWII, fresh demand for coal sent the miners back down dilapidated shafts to dig. The pits were plagued by fatal accidents, and poor construction, paired with amateur diggers after the experienced miners went off to war, continued to degrade the land, people, and settlements. Below is a picture of Franklin, with row shanty housing built atop mining tails, and empty rail lines.

White colonial narrative and ownership weaves a toxic trail of resource extraction left by careless plunderers and labor abuse practices. Though the river today looks quite breathtaking, and the gorge holds deep etchings of geologic time, scars of mining, railroad, logging, and abandoned settlement remain haunting reminders of abuse the landscape endured through industry. The area’s natural beauty was preserved in 1973, after the last active coal mine closed in 1971. Still, the land had been raped by industry, and such violent treatment of the earth caused long lasting consequences for the miners, their families, and the surrounding population though the generations. None of the commercial entities which originally founded the mines are around today to take responsibility, yet today’s companies float a similar river of greed with no care of human or ecological devastation. Who’s still buying most of what they need from said corporations? *raises a hand*

For our outing into this history, we walked Franklin’s overgrown streets, where domestic roses twine up young alders and through old stone and brick foundations. Arsenic seeps out of the old coal seams, and it was that neighboring chemical poison, which ultimately killed many people in Franklin and forced the abandonment of the town. Today, down the mountain from the old mines, there is a natural spring many people gather water from, yet no one seems to care about the surrounding toxic nightmare that slowly continues seeping into the groundwater. Shanty villages of broken down RVs and blue tarps nestle nearby. Many of these destitute people can trace their lineage back to miners who were exploited by industry, just like the land.

From the mountain that once hosted Franklin, you can look out across The Green River Valley and still see corporate greed at work tearing up the landscape and building elaborate structures to propel profit for the few at the cost of many. What really struck me, in the one night we spent in the area, was the energy which spoke volumes of the abuse and pain still flowing through the river today; nightmares. I had very unsettled dreams, full of miserable people waiting in long lines to get a pay check, or struggling to get out of the mud, children crying and women screaming, it was palpable. Many people received violent deaths in the mines, but many more were slowly poisoned by the pollution of the pits, and the arsenic released by their digging. Green River Gorge is a beautiful river today, but the surrounding history of extraction haunts the hills with ghosts long troubled by greed and carelessness.

If you find yourself in the area, bring something to smudge with, and expect disturbed sleep, as the unrest in Franklin continues, along with the legacy left by careless taking and giving nothing but destruction in return. Now the state is left to continue cleanup, and though there are some nice walking trails and mountain views, the soil is soaked in coal ash and littered with the ghosts of people swallowed up by the mines or sentenced to slow death by poison. Such abuse still persists into modern times, though now instead of mines we have microplastics.